As an endodontist and peer advisor, I am commonly asked what my patients are told prior to commencement of treatment and how to answer the dreaded question – ‘how long will the tooth last me?’ Therefore, in this article, warnings to patient regarding endodontic treatment as well as ‘real-life’ success and failure in endodontics will be explored.

There is no doubt we as clinicians have a duty to warn patients of possible adverse outcomes as a result of treatment – broken endodontic instruments, failed implants, fractured restorations, paraesthesia post-surgery, to name but a few, are all possibilities and retrospectively the patient will often come back to us with the statement “I was never told….”

However, how are we expected to accurately predict all possible permutations? Do we sit down with the patient and spend hours outlining ALL possibilities? In all likelihood, by the time we’re done, we would have succeeded in alarming the patient to the extent that every tooth would be removed and they would probably remain edentulous!

So, what as a profession are we doing to deal with this dilemma? We produce information sheets and consent forms (the length and detail of some which would make the legal profession proud!), give them to the patient to read and sign, file it away and feel safe in the knowledge the patient has that piece of paper.

But what value do the courts place on such forms? Sorry to say folks, not much… it is a piece of documentary evidence, is only useful if there’s doubt about whether the patient has agreed to go ahead with the procedure and not, in itself, determinative of the issue – to quote a law text:

‘Even if the form states that the patient acknowledges that he or she has been fully informed and given the opportunity to ask questions, the patient may still be able to persuade the court that was not the case’.[1]

…and don’t think this dilemma rests solely with the dental profession. In a High Court case in 1998, Chappel v Hart, Dr Clive Chappel, an ENT specialist, operated on Mrs Beryl Hart in June 1983 following the patient’s complaint of acute dysphagia – an extremely painful condition with difficulty with swallowing. The cause of her symptoms was a ‘pharyngeal pouch’ – ‘an uncommon pathological outpouching of the pharyngeal mucosa through a weak area of the pharyngeal wall (Killian’s dehiscence)’.[2] Surgery was her only treatment option.

Two surgical treatment options were offered:

- surgical excision of the pouch via a cervical incision or

- the septum between the pouch and the posterior wall of the oesophagus is divided endoscopically. The cricopharyngeal muscle is then severed, thereby widening the oeophagus (‘the Dohlman operation’).

Professionally, Mrs Hart was an education officer (teacher) and thus at consultation told Dr Chappel she did not want to ‘end up sounding like’ Neville Wran, the NSW Premier at the time who had developed a severely hoarse voice as a result of throat surgery.[3]

The Dohlman procedure was carried out on 10 June 1983 and the patient advised there was a 6-18% chance that a perforation of the oesophagus may occur as a result of using an endoscope, but not of the slight risk that her voice may be affected as a result.

Needless to say, the perforation occurred – on recovery, the patient complained of hoarseness and was diagnosed to have developed vocal chord palsy (VCP) as a result of the oesophageal perforation site becoming infected, thereby damaging the recurrent laryngeal nerve (which anatomically is remote from the surgical site).

Mrs Hart, as a result of the procedure and subsequent vocal chord palsy, was compelled to take an early retirement as an Education Officer. She commenced legal proceedings in 1989 and went to trial in 1994 at the NSW Supreme Court with Donovan AJ presiding. Justice Donovan found for the plaintiff – that Dr Chappel had indeed breached his duty by failure to warn of the risk of VCP – awarding Mrs Hart $172,500 in damages.

The defendant was granted special leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia in 1998, the justices dismissing the appeal by a majority of 3:2.

This case is unique in that the end result was one where the surgeon performed a procedure to a standard without criticism from peers and that the (unfortunate) outcome was one that was extremely rare and, argued by some, that the doctor was in no position to warn of that outcome. In a recent article, Thomas Hugh argued that the complication of VCP following the Dohlman procedure suffered by Mrs Hart had never been reported in the literature. Therefore, ‘the complication about which Dr Chappel was supposed to have warned the plaintiff had never been reported prior to Mrs Hart’s operation…and…remains to this day the only recorded case of Dohlman-related VCP’.[4]

But did the High Court get it right here? I actually think they did. The key to this case was Mrs Hart’s extreme apprehension as to what impact the procedure may have on her voice. As Justice Kirby described it, the protection of the integrity of the patient and improved health care by warning patients about material risks (especially when they are apprehensive and query outcome and adverse effects) is a ‘rigorous legal obligation’[5] of the health profession.

As the justices in Rogers v Whitaker stated in 1992:

‘The law should recognise that a doctor has a duty to warn a patient of a material risk inherent in the proposed treatment; a risk is material if, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient’s position, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it or if the medical practitioner is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient, if warned of the risk, would be likely to attach significance to it’.

As Professor Skene notes, as a result of the decision in Rogers v Whitaker, ‘patients are entitled to make their own medical decisions and that the information necessary to make that decision varies according to the patient’s own circumstances. It cannot be determined in advance by an objective test or by accepted medical practice’.[6]

So what is a material risk in dentistry (specifically here in endodontics) and how do we know if the patient will attach significance to it? Giving your patient a 5-page disclaimer and series of bulleted warnings is certainly not the answer.

The answer of course lies with frank and open discussion with the patient and, as health care professionals, our duty lies in ascertaining where our patient’s concerns lie and what we as clinicians feel may be significant from the patient’s perspective. Some examples are extremely curved canals (file fracture?), calcified canals (perforation?), third molar impactions adjacent to the IAN (paraesthesia?), poor bone density (implant failure?).

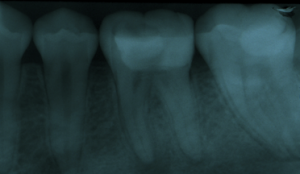

In cases such as this (above), what needs to be discussed with the patient? Note the sharp curvature of the MB root, the receded pulp chamber and fine canals. As a clinician, my duty here is to advise my patient of the complexity of the case. Issues such as potential file fracture, possibly not negotiating all the canals (and its significance) and potential for perforation (although unlikely) should all be discussed.

On the other hand, in cases such as the one illustrated below, it may not be necessary to discuss the same issues as above. However, if the patient is inherently curious about different aspects of treatment, alerts you to this fact by asking a series of pertinent questions related to failure, possible file fracture etc, then, according to the ‘material risk’ test, it is important to outline and address all the issues raised, even if the outcome (from a clinical perspective) appears remote:

Indicating in your records ‘patient warned of risks’ therefore is not good enough. From a dental defense perspective, details of the conversation should be recorded. For example, ‘discussed with patient if crown not placed following RCT then great risk of fracture and possible tooth loss’.

This is far more convincing when presented as evidence rather than stating retrospectively that you ‘recall discussing with the patient’. As a judge in the Victorian Court of Appeal recently stated in reference to an oral surgeon’s tendered evidence of his recollection of his discussion with his patient:

‘Even were I to accept his version of what was said — and I do not in its entirety – because it is so very heavily reliant on reconstruction…’[7]

The duty to warn therefore is paramount to clinical practice. The paternalistic approach of practitioners is long gone (as it should be) and therefore when discussing possible risks of treatment, the practitioner must look beyond the tooth and take into account the patient’s concerns and apprehension.

Prognosis

Just as discussing possible risks of treatment is important, the subject of prognosis needs to be discussed with the patient both objectively and subjectively. Endodontic treatment, probably more than any other discipline in dentistry, has been subjected to a number of success and failure studies. In turn, these findings are published in the literature and subsequently quoted by clinicians to their patients.

Sjogren et al (1990)[8] is one study that is probably quoted most frequently. When asked by a patient what the likelihood of success of treatment is to be, clinicians, regardless of experience and techniques employed, will quote Sjogren’s findings:

- 96-100% – ‘vital’ cases

- 82% – presence of periapical pathology

- 62% – re-treatment with periapical pathology

Quoting such figures can be fraught with danger. It is imperative to bear in mind how the Sjogren study results were obtained – all the teeth presented and reported on were treated under meticulous bacterial control conditions, including rubber dam, irrigation with appropriate irrigants and canal medication.

It is unlikely the straightforward case illustrated below will eventually succeed. Lack of rubber dam and inadequate access will likely lead to treatment issues and have a negative impact on long term success…but in all likelihood, prior to commencement of treatment, this patient was told that the success rate of such treatment would be somewhere between 90-95%.

Therefore, I would suggest dentists refrain from giving patients even broad success rates – the higher the percentage, the more likely it will NEVER be forgotten by the patient (and the clinician will constantly be reminded post-failure!) Like risk analysis and assessment, prognosis should be discussed on a case-by-case basis.

Which then brings the clinician back to the importance of the pre-operative assessment. The American Association of Endodontists has available from its web page (www.aae.org) a PDF download of guidelines for assessing the difficulty of endodontic cases.[9] Although it is slightly prescriptive in nature, it assists the clinician to carry out an extremely thorough and systematic analysis of the case prior to embarking on treatment. As such, prognosis and associated risks of treatment can be discussed in detail.

In summary, consent forms and information sheets do play an important role in day-to-day clinical practice as part of the consultation and treatment planning process. However, they should not be seen as a panacea in protecting the dentist from litigation and consent issues which may eventually arise. Careful pre-operative assessment, open discussion with the patient and, of course, a signed consent form all assist to ensure the patient (and you as the clinician) are in a comfortable position to deal with any issues which may arise during the course of treatment as well as in the future.

Issues such as consent and patient management (when things go wrong!) can be confusing and, in many instances, distressing for all parties. If at any stage you have a question or wish to discuss a particular case, please feel free to contact David Sweeny, Peter Crozier, Roger Dennett or me at the DDAS – we all enjoy assisting whenever we can and sometimes it just helps to have a third party to lean on!

Dr Stephen Harlamb BDS, MDSc

Peer Advisor, ADA NSW

[1] Law and Medical Practice. 3rd Ed, L Skene 2008, p.90

[2] <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharyngeal_pouch> accessed August 30 2009.

[3] Thomas Addison, ‘Negligent failure to inform: Developments in the Law since Rogers v Whitaker’ (2003) 11 Torts Law Journal 1 at 9.

[4] Thomas Hugh, ‘Surgical Sense and Legal Non-Sense – Chappel v Hart revisited’ (2009) 79 ANZ Journal of Surgery 554 at 555.

[5] Chappel v Hart (1998) 195 CLR 232 at 272 (Kirby J).

[6] Ibid. pg 179.

[7] Hookey v Pantero VCOA 2009

[8] Sjogren et al 1990 JOE 16:498-504

[9] http://www.aae.org/dentalpro/CaseAssmtReferral.htm