The Biblical figure King Solomon lived between 1000 BC and 931 BC. The Bible portrays him as great in wisdom, wealth and power. One of the qualities most ascribed to Solomon is his wisdom. There is a famous account demonstrating this, wherein it was said that Solomon suggested dividing a baby in two to determine its real mother. In this often-quoted passage, two prostitutes came before Solomon to resolve a quarrel about which of them was the true mother of a baby. The other’s baby died in the night and each claimed the surviving child as hers. When Solomon suggests dividing the living child in two with a sword, the true mother is revealed to him because she is willing to give up her child to the lying woman rather than have the child killed. Solomon then declares the woman who shows the compassion is the true mother and hands the child to her.

An oral surgery mentor of mine once replied to my question “Why are third molars called wisdom teeth?” with the answer “Well, in my opinion it is because you need the wisdom of Solomon sometimes to know which ones you should remove and which ones you should leave”.

In any event, we have to say that wisdom teeth are not like Mt Everest! The celebrated mountaineer, George Leigh Mallory, is famously said to have replied to the question “why do you want to climb Mt. Everest?” with the retort: “because it is there”. Well, certainly third molars don’t necessarily need to be taken out, just “because they are there”! The decision to surgically remove or not to remove wisdom teeth is sometimes a complicated one, given the many factors which may be relevant to the decision. Fortunately, if I am proud of one thing about the dental profession, it is the universal willingness of experienced practitioners to assist their colleagues when they ask for help. Perhaps the reason for this may lie in the universal wish to help them avoid the same mistakes that they themselves may have made in their younger years!

But I digress. This article is a case report of a recent case concerning a Dental Board complaint which was lodged by the family of a young man who had presented with some anterior crowding in the upper arch. His mother was especially concerned about a buccally drifted upper anterior tooth, tooth 21.

Consent

To address the patient’s chief complaint, the dentist, Dr X, discussed various options to correct the rotated and labio-versed tooth 21. The patient stated his aversion to full fixed orthodontic therapy. Further orthodontic options were given, which were not well received. Finally the mother and the boy decided that the only acceptable option for them was to have the four impacted wisdom teeth surgically removed. They were both keen to have this done as soon as possible, notwithstanding the approaching HSC examinations.

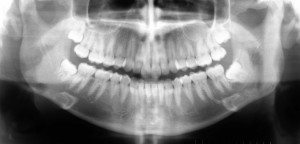

In discussions with the practitioner, it is interesting to note the mother of the boy was advised that it was not medically or dentally necessary to surgically remove the wisdom teeth, as the teeth were not causing any pain or infection. The dentist’s advice was that it was the mother’s decision entirely as to whether to have the four wisdom teeth surgically removed. The dentist suggested that any such operation should of course be left until after the HSC exams. However, the boy stated that he preferred it to be done before the HSC as he was going on a “schoolies’ cruise” immediately after the HSC. At this consultation appointment, the OPG was displayed and the relationship between the mandibular canal and the apex of the lower wisdom teeth was demonstrated to them. At this time, the practitioner warned of the risks of the operation. He stated:

“When we take out the wisdom teeth there is a small chance of damaging the nerves to half of your face, lip and tongue, including taste. If this happens, you may end up with numbness to these areas. Whilst this may last for only three to six months, in the worst case, it may be permanent”.

The patient’s family was then given the opportunity to ask questions, and then finally signed the hospital GA consent form, which stated in simple terms that they understood and accepted all the risks of the operation and consented to it, having had the opportunity to ask questions which were answered to their satisfaction.

The procedure

Some two weeks later, the operation was carried out under in hospital under general anaesthetic. The surgery was uneventful as they were routine surgical extractions in a young patient with minimal bone removal. No tooth division was necessary. Regarding the removal of tooth 48 (the tooth in question), the dentist raised a standard envelope flap, removed some buccal bone with a surgical handpiece under saline irrigation, after which the tooth was then elevated out quite easily using a Coupland elevator. Two silk sutures were placed over the wound. The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and anti-inflammatories.

Post operation

The practice (a member of the staff) called the patient the following day but was unable to speak to him and so left a message on the home phone. The patient returned the call subsequently and attended for review four days later. The sutures were removed. Whilst there was no sign of any infection, the patient reported “tingling and numbness” on the right hand side of his tongue. It was noted that there was no numbness associated with the lip, chin or face. The dentist considered that the numbness was likely to be temporary, and he informed the patient that this was most likely due to the post operative inflammation around the lingual nerve. The dentist reassured the patient and his mother that the sensation would likely return in three to six months as explained prior to the surgery.

One week later, the patient attended reporting that the numbness had improved since last time. The dentist noted that there was normal sensation in the region of the anterior distribution of the nerve. This reinforced his view that sensation would continue to improve and was only due to post operative inflammation around the lingual nerve.

A subsequent review appointment was made three months post- surgery but this appointment was never kept.

The Dental Board complaint

The mother of the patient lodged a complaint with the NSW Dental Board. In the complaint, she stated that she had subsequently sought a second opinion from an Oral Maxillofacial Surgeon, and that opinion seven months post operatively was that the numbness suffered was permanent. In the complaint, the mother stated that her son had missed a “window of opportunity” to have the nerve surgically rejoined, which she had learned was a period of some four to six weeks. She further stated that at no time was she informed by Dr X that the numbness was permanent.

In response, Dr X countered that the patient was seen five days post-operatively, and again one week later. At this second post-op visit, it was noted that the numbness had improved about 30% since the last visit. This reinforced Dr X’s view that the numbness was due “to the post operative inflammation around the lingual nerve” since there was normal sensation in the anterior region of the nerve distribution. The patient was then seen again some three months post operatively. Dr X’s practice also called the patient to review progress on a couple of occasions within this time period. In relation to the mother’s statement that she had not been informed that such injury might be permanent, Dr X countered that this very possibility had been explained to them on the initial consultation prior to the surgery.

The Board referred the matter to the Dental Care Assessment Committee for investigation. The matter was referred to an experienced independent assessor, who was critical of Dr X’s management, stating:

’….if recovery had not been noted within a four week period, further evaluation of the injury was warranted…..the opportunity to evaluate the injury should have been given to the patient through timely referral and in this regard I find the required knowledge of nerve injury management was lacking in our colleague. The risks and benefits were not for him to decide upon and timely referral would have been the correct procedure…..It is my opinion that Dr X underestimated the nerve injury and appears to lack appropriate knowledge as to nerve injury physiology and prognosis…..On the challenging subject of prolonged paraesthesia and nerve repair, I believe that Dr X has to update/revise existing knowledge relating to the treatment of neural complications.”

The Committee was further critical of Dr X’s decision to remove the teeth, stating that there was little or no evidence to support the notion that third molars contribute to crowding particularly of upper teeth, and that he should at least have sought a second opinion prior to making a final decision. The Committee further opined that, far from acceding to the patient’s subjective choice if he wanted the wisdom teeth removed, the dentist had every obligation to refuse treatment if there were grounds for doing so, as they felt there were in this case. They were also critical of the decision not to refer on when the patient experienced post operative numbness.

The Committee recommended to the Board that Dr X refund his fees and undertake a refresher course in “applied anatomy”, to be determined by the Board. They called Dr X to a meeting of the Board where they would be considering whether this matter constituted “unsatisfactory professional conduct.”

The Board hearing

Dr X, with the assistance of the DDAS Peer Advisor, had prepared a Statement to be read out to the Board. Dr X stated his case and was able to explain his treatment decisions. He gave evidence that, rather than ignoring the paraesthesia, there was quite a reasonable follow up of the patient after the surgery. He restated that he was of the view at the time that the paraesthesia would continue to improve and therefore deemed that no referral to a specialist colleague was necessary. However, Dr X did acknowledge that he had learned from the experience and he now recognized that he should have referred the patient for timely investigation in regard to the paraesthesia within the first few weeks.

Dr X was subjected to what could only be described as a barrage of questions from a number of the Board members. The questions included his understanding of the path of the lingual nerve. He was asked to describe his surgical technique in this case. He was questioned about the appalling timing of this operation, shortly before the HSC examinations. He was asked whether in his opinion that the teeth needed to be removed at all. He was informed that literature reviews since 2000 have consistently stated that there was no evidence of a connection between wisdom teeth and upper anterior crowding. When asked why he had delayed referring the patient to a specialist surgeon, Dr X said that it was his training as an undergraduate (less than 10 years experience) to allow some three to six months for these injuries to repair. Dr X was able to quote a study which indicated that such injuries usually resolve over this time period and that surgical intervention was not required. The response of the Board to this was that this study was now considered to be out of date and the knowledge in this area had changed.

After considering their verdict, the Board resolved that the complaint did not raise issues of unsatisfactory professional conduct, and therefore dismissed the complaint. However, they issued Dr X with a strong reprimand. On one hand, the Board said that they accepted that Dr X had provided options for treatment. They accepted that in the circumstances of the case that it was not outside the parameters of accepted treatment that such surgical removal should be or could be performed by a general dental practitioner. They were of the view that the complaint was not about a lack of surgical skill nor was there any statement from the independent assessor that an inappropriate incision or surgical technique was used.

However, the Board commented that Dr X needed to be aware of the following:

- That the timing of the operation, coming just before the HSC, was appalling and should have been avoided, notwithstanding the patient’s direct request.

- That in such a situation, it would have been better if Dr X, as a relatively inexperienced practitioner, had sought a second opinion from a more experienced colleague before deciding to go ahead with the procedure given the circumstances of this case.

- That is was not only appropriate to refuse to carry out the treatment for the patient, but that Dr X should accept that he owed the patient the professional responsibility of not performing a procedure that he didn‘t feel was or might not be in the patient’s best interests. The Board stated that this was especially the case when considering surgical treatment where there was likely to be little benefit for the patient.

In saying this, there is always the decision to be made that the benefit of the treatment outweighs the potential risk. Whilst in this day and age this is indeed in part a consumer’s right to decide, it is behoven upon all practitioners to accept that sometimes no treatment may be the best treatment in situations where there is little or any benefit likely to be gained by carrying out any given procedure.

The Board made reference to the 2002 annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, and that Dr X, as a Fellow of the College, should study four articles published therein. I have taken the liberty of locating those and some additional relevant articles and have included these as a reading list at the end of this article. They are available through the ADA NSW Library. Members can contact the Librarian, Gael Ringuet on 8436 9960.

Comment

Lingual nerve injuries present one of the most compelling dento-legal issues. The issue stimulates intense debate. Reports from previous studies have indicated a large variation in the incidence of nerve injuries ranging from low of 0.6% to a high of 22%. In general, studies from the UK have indicated a higher incidence of lingual nerve injuries than those from the US or Australia. This has been attributed to the technique of raising lingual flaps[3] and the popularity of the lingual split technique. Some oral surgeons believe that damage to the lingual nerve, of itself, indicates negligence in the procedure. However, the majority of oral surgeons consider that lingual nerve damage can happen in the most competent of hands, but is less likely to happen in the hands of a skilled and experienced oral surgeon. Certainly the experience of the DDAS is that such injury does occasionally happen in the very best of hands, and for reasons which are not clear to the operator.

There is considerable evidence that the lingual nerve is variable in its size, shape and course. All clinicians working in this area must assume that the nerve is very close to the lingual plate of bone and the gingival margin of the lower third molar. In a comprehensive study of 34 dissections and 256 cases of mandibular third molar extractions[2], 17.6% of lingual nerves were at the level of the alveolar crest, or higher! The study found that 62% of lingual nerves contacted the lingual plate of the lower third molar. These data provide sobering evidence that the lingual nerve is highly vulnerable in this area, endangered so frequently during routine third molar surgery.

Nevertheless, general dentists and specialists alike usually express complete surprise at the lingual nerve being damaged, despite the use of standard, accepted techniques. In light of the uncertain occurrence of this complication, the duty to warn is paramount. Ask yourself – what would a patient want to know about this? Would you want to hear about absolutely every possible unfortunate sequelae, no matter how minor? I would suggest no. Would you want a lesson on the path and morphology of the lingual nerve? Maybe perhaps. But in reality most patients would want to know what may happen and what they will feel like if it does happen. Leggatt[8] has suggested the following warning:

“The lingual nerve supplies sensation to the front two thirds of your tongue. You have two of them, one on either side. Occasionally, they can be damaged during extraction of your lower wisdom teeth by instruments coming into contact with the nerve. This can cause temporary or even a permanent change in or loss of sensation to this area. This means that you could have a numb tongue for the rest of your life. There is a small risk of this happening. That risk could be further reduced if you wish to consult an expert Oral Maxillofacial Surgeon.”

Obviously, the last part is for general dentists only, but again this stresses an important point. As a patient, is it not reasonable to know that there are specialists who can do the same procedure? To quote Leggatt[8]again:

“This is at the core of most dental and medical litigation. Most patients with a damaged lingual nerve understand that mistakes can happen. What they do not readily comprehend and have difficulty in accepting is the feeling of being lied to. Of not knowing that this is a recognized complication. Of not knowing that there were specialists who could have possibly reduced the risk.”

In the Board case referred to above, the Board was critical of the lack of a written warning. Dr X relied on verbal information and referral to a website. He was told by the Board that this was inadequate in this day and age and that it was the standard of care to provide such warnings in writing. Therefore dentists should consider having the patient sign a form acknowledging the warning provided as part of the consent process.

On this note, the DDAS often receives requests for a “pro-forma” consent form that will provide dentists with complete protection against such complaints. There is no such thing. In the words of Prof. John de Burgh Norman, informed consent “is a process, not a form”. The issue is to communicate with the patient so that they can accept what has happened to them if their lingual nerve is damaged.

The DDAS Peer Advisors can be contacted through our office Coordinator, Katherine O’Sullivan, on 8436 9944. We are available at any time to discuss this and the other many issues which arise during the day-today running of a busy dental practice. We look forward to speaking to you!

Dr Roger Dennett (Peer Advisor)

Dental Defence Advisory Service, ADA NSW

Bibliography – Third molar and nerve injuries – Annals of the RACDS 2002.

[1] The effect of orthodontic treatment on third molar space availability: a review.

Sable Daniel L

School of Dental Science, University of Melbourne, Victoria.

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( Australia ) Oct 2002 , volume 16 pp156-157

[2] Anatomy of the lingual nerve in relation to possible damage during clinical procedures.

McGeachie John K

Oral Health Centre of Western Australia. [email protected]

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( Australia ) Oct 2002 , volume 16 pp109-110

[3] Nerve injuries following the surgical removal of lower third molar teeth.

Rix L

Department of Oral Surgery, United Dental Hospital, Dental Faculty, University of Sydney.

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( Australia ) Oct 2000 , volume 15 pp258-60

[4] What is the future of third molar removal? Removal of impacted third molars–is the morbidity worth the risk?

Woodhouse B

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( AUSTRALIA ) Apr 1996 , volume 13 pp162-163

[5] What is the future of third molar removal? A serious presentation for not performing the removal of third molars.

Sinclair J H

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( AUSTRALIA ) Apr 1996 , volume 13 pp158-161

[6] What is the future of third molar removal? A critical review of the need for the removal of third molars.

Anker A H

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( AUSTRALIA ) Apr 1996 , volume 13 pp154-157

[7] The mandibular infected buccal cyst–a reappraisal.

Thurnwald G A; Acton C H; Savage N W

Royal Brisbane Hospital, Australia.

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( AUSTRALIA ) Apr 1994 , volume 12 pp255-263

[8] The legal implications of lingual nerve injuries.

Leggatt David

Phillips Fox, Melbourne, Victoria.

Annals of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons ( Australia ) Oct 2002 , volume 16 pp115-117